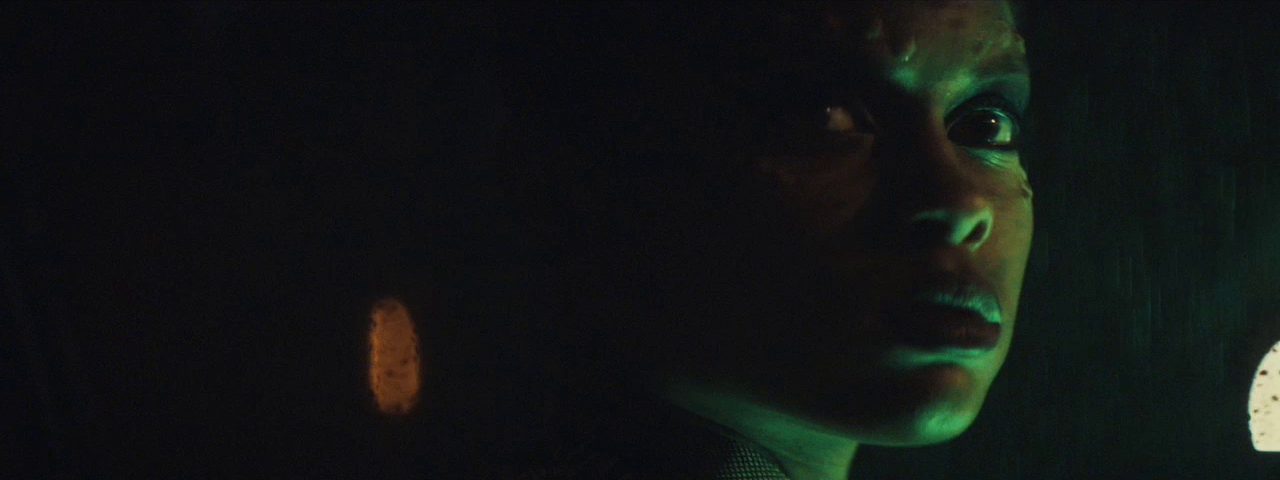

Casey Tebo’s Black Friday with Bruce Campbell (The Evil Dead), Devon Sawa (Final Destination), and Michael Jai White (Spawn) is almost done shooting. And recently, Sawa told us exclusively that the new film is bonkers, hysterical, and frightening.

Sawa tells Dread Central: “We’ve got two weeks left so we’re coming to an end. Bruce and I have done many many scenes together and so has Michael Jai White. The movie is bonkers and frightening. It’s going amazing. They’re getting great stuff. I couldn’t be happier. This is the first time I’ve felt like I’ve done one of these kind of movies since Slackers or Idle Hands. It fits on that shelf.“

Read our full interview with Sawa HERE.

He adds: “Bob Kurtzman is the special effects guy and he’s done everything… He’s one of the masters at this, and they put a lot of money into the special effects, and he built some very original stuff. We’ve got everything from animatronics to big tall guys in old grandma suits. It’s nutty. It’s nutty and hysterical and frightening. Bruce is being this different character that I’ve never seen him play. Michael Jai White is kicking a little bit of ass so it’s all there, man.”

Set on the busiest shopping night of the year, Black Friday follows disgruntled toy store employees who have to defend themselves from legions of holiday shoppers when a mysterious alien parasite sends them on a murderous rampage.

Warner Davis produces Black Friday from a screenplay by Andy Greskoviak, the film co-stars Ivana Baqureo, Ryan Lee, and Stephen Peck. We’ll make sure to keep up to date on this sure-to-be must-see flick and pass along new info as we hear it.

Stay tuned.