As a cinematographer, you’re usually only involved in the creative process immediately prior to, and during, production. Occasionally, if you’re lucky, you’ll also be brought in to work with a colorist on the final DI, which these days does not happen often. It almost never happens that you get to be involved in the entire process from start to finish, but as I have stressed before, filmmaking is a collaborative art, and having creative collaborators that you trust as much as they trust you, although rare, is truly an extraordinary thing.

Director Mike Pecci (@mikepecci) approached me at the very beginning of this project. Before he knew what the story would be, who would be cast as talent, or what products would be showcased, he called me up and told me that Dalstrong had given him a budget and to make something cool, and wanted my help. Mike and I have worked on an extensive list of projects together, and one of my favorite parts of collaborating with someone I trust is that ego is left at the door. If he asks me for creative suggestions, it doesn’t mean I’m trying to take his job. If he suggests a way to light or shoot something, it doesn’t mean he’s trying to take mine. This is entirely about coming out of this process with something that we are both incredibly proud of.

We started discussing ideas and one aspect we explored immediately was casting. The chef we had worked with previously on a different Dalstrong campaign had since moved out of state. Another chef that we both admire (and local to the Boston area) was so slammed running three restaurants that we would never have been able to schedule the shoot in a reasonable manner. But it just so happens that I had an incredibly talented chef in the family: my brother Philip, chef/owner of Brassica Kitchen in Jamaica Plain (@brassicakitchen).

The Talent

We called him up and he was immediately in to the idea. A former filmmaker himself, he was familiar with the process and excited about all the ways he could help. As we started talking about the ways we could portray his food and knife work, another exciting creative opportunity showed itself - his woodworking. Phil is an incredible woodworker, and built a lot of his restaurant by hand. The overarching elements of the story were there, but we needed to unite them in a way that would tell a story and portray the brand positively.

In the spirit of collaboration, we reached out to another person that I’ve had the pleasure of collaborating with numerous times: writer, director, and former (always?) creative, Patrick Biesemans (@patrickbiesemans). He didn’t hesitate to say yes, and within days had written the first pass at the voiceover, which would ultimately become our guideline for what we would capture on camera.

The Idea

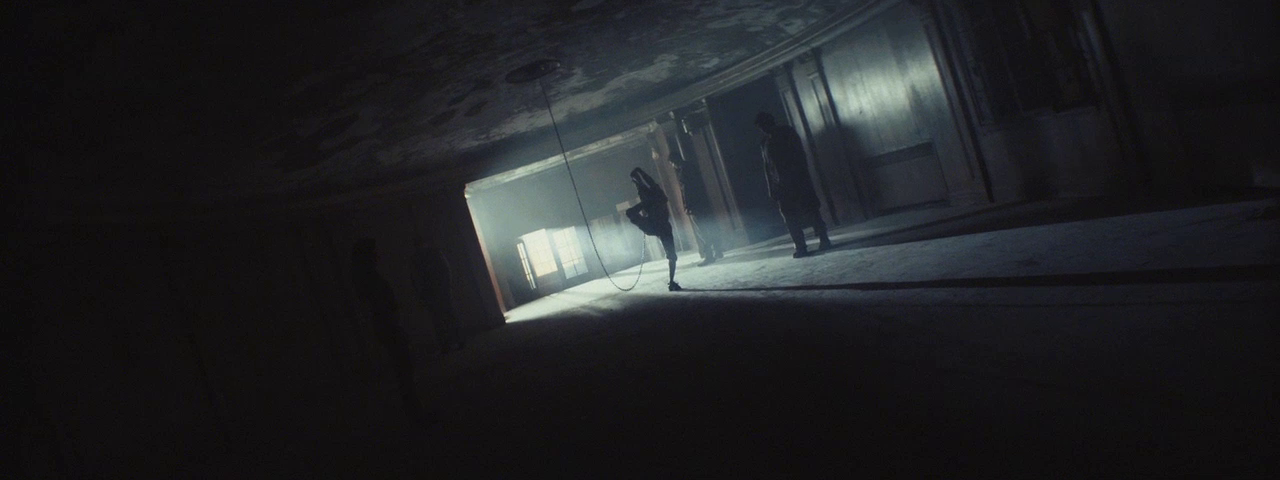

Patrick’s outline focused on the abuse our hands take from the daily rigors of working with wood and with food. It portrayed perfection as something born from abuse, hard work and diligence. It looked at taking rough, raw materials and turning them in to a thing of beauty.

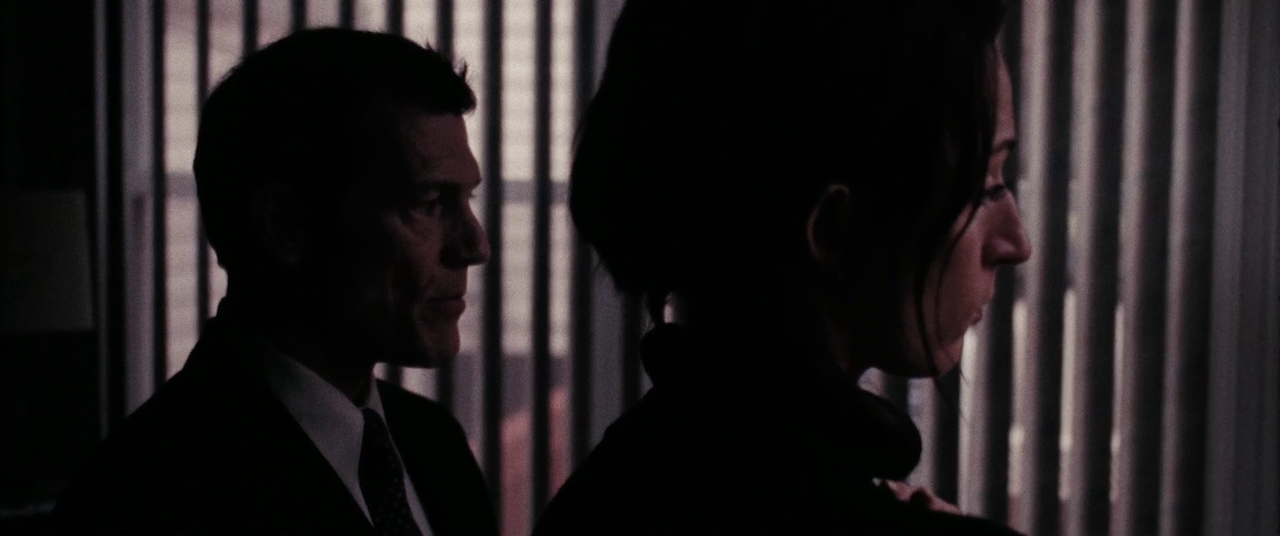

I found many parallels between that and my own work with Mike. We spoke for hours over numerous phone calls about how to create the visuals for this spot, because we wanted to touch on all these aspects with the images you would see on screen. There had to be rough, chaotic, contrasty scenes, mixed with energy, refinement and beauty. We have shot extremely stylized spots in the past, as well as more subdued and polished ones, but this was an opportunity to show both what we could do, while holding true to ourselves as filmmakers.

The Execution

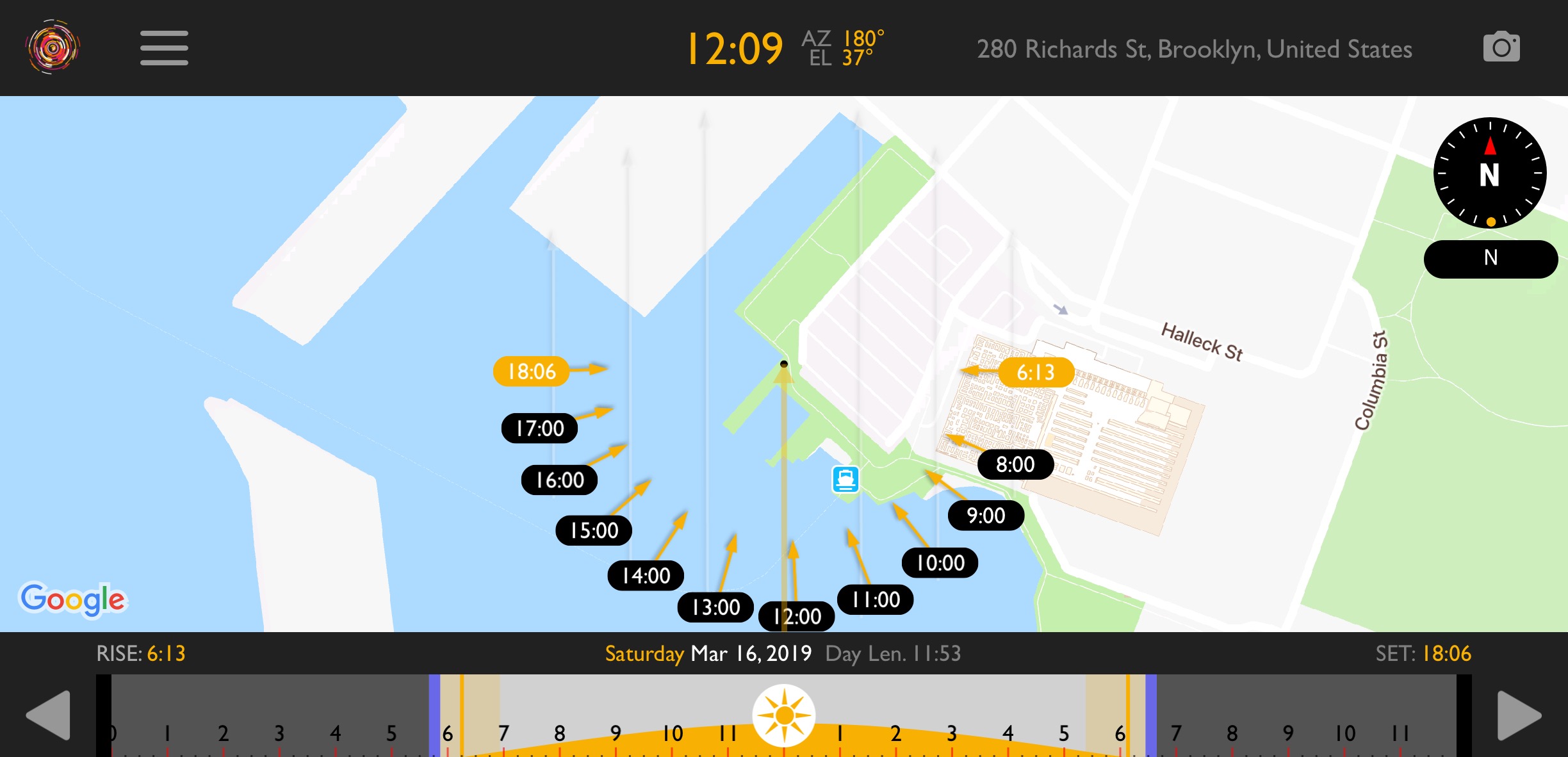

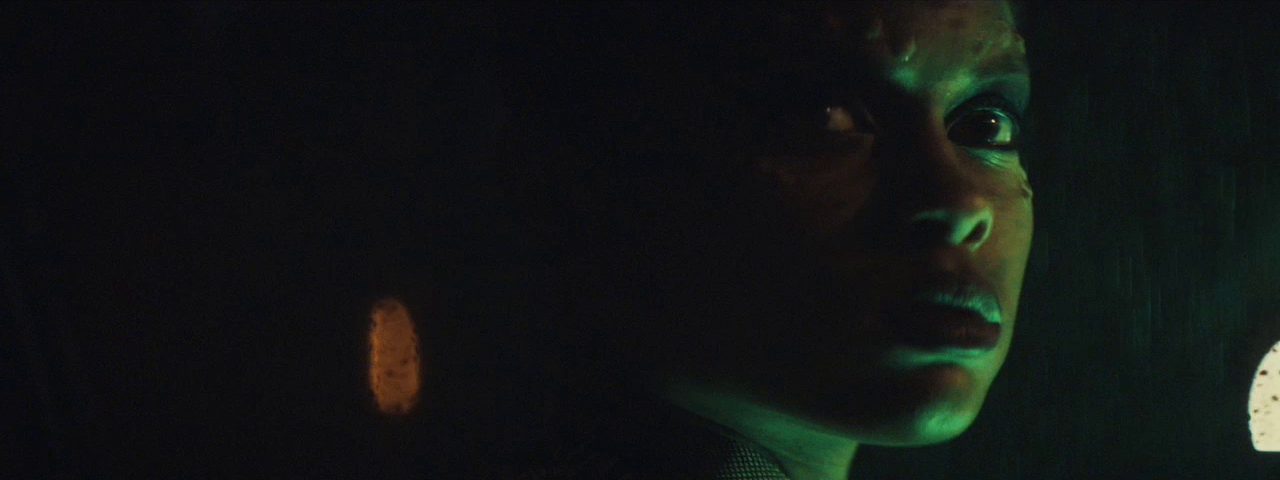

Having decided on building out three different worlds, with a single thread in the form of lighting cues to tie them all together. These would be the workshop, the restaurant, and the void, where our chef would be cutting, cooking and plating against a black background. We started by passing visual references back and forth, from which I could build out our lighting plots.

Due to time and talent availability restraints, the location work had to stay minimal. We lit mostly with a set of Astera Titan tubes, supplemented with a Joker 400 and some canned haze. This lent itself well to the “real life” look of the locations, and allowed us to focus our efforts on the stage work. Gaffer Ruben Alves and his crew set up a box of 20x20 solids, a Skypanel S30 on a menace arm, and the Titans so that we could jump from one setup to another with ease.

When lighting food, I like to use a large, soft source either from above or off to the side to mimic a window. Not only does the size of the source allow for it to wrap around the food and fill in the shadows, it also creates a reflection. A light glaze on the food emphasizes this, and these two qualities together make it look lively and appetizing. A lot of us in the field of cinematography love to use darkness and shadows, but this is an instance where softness and fill can work to your benefit.

We shot on the Alexa Mini with Cooke Anamorphic/i lenses, a departure from the Lomo Square Fronts that Mike and I usually shoot on together. The reasoning behind this was that we wanted to retain our style that usually involves anamorphic lenses and aberrations, but to bring some modern polish to the rest of the spot. The Cookes are a wonderful set of lenses that retain some of that vintage character, especially wide open, while being much sharper and mechanically forgiving than the Lomos.

Post Production

As the spot was being edited, Mike was inspired by the sound design and voiceover from the Avengers: Endgame trailer, and used that as a rough track to cut to. He sent me the first rough cut, and we agreed that we loved the simplicity of it.

Although Patrick had written a beautiful monologue to accompany the spot, we had to go back to the drawing board. This is where ego could have easily come in, but again, with great, trusted collaborators, there is nothing but a desire to create the best work we can. He agreed with where it was headed, and rewrote and reworked the voiceover until it became what you hear in the final spot.

We were lucky enough to have one more collaborator in the room (literally): Rob Bessette (@robsbessette), colorist at Finish Boston, who threw himself into the project with an enthusiasm that gave us the energy to finish the piece with a bang. We pulled a single marathon session and went through each frame, building a color palette that would evoke different emotions in each scene, while guiding your eye to the relevant parts of the frame and taking you through this journey of craftsmanship, passion and perfectionism.

Although I wasn’t able to work with him directly, the music by Code Elektro tied the whole piece together. Check him out on Instagram at @code_elektro.

As always, the conversation continues on my Instagram (@dkruta). Please feel free to send me any questions or comments. I love chatting about cinematography and I’m always interested to hear your thoughts.